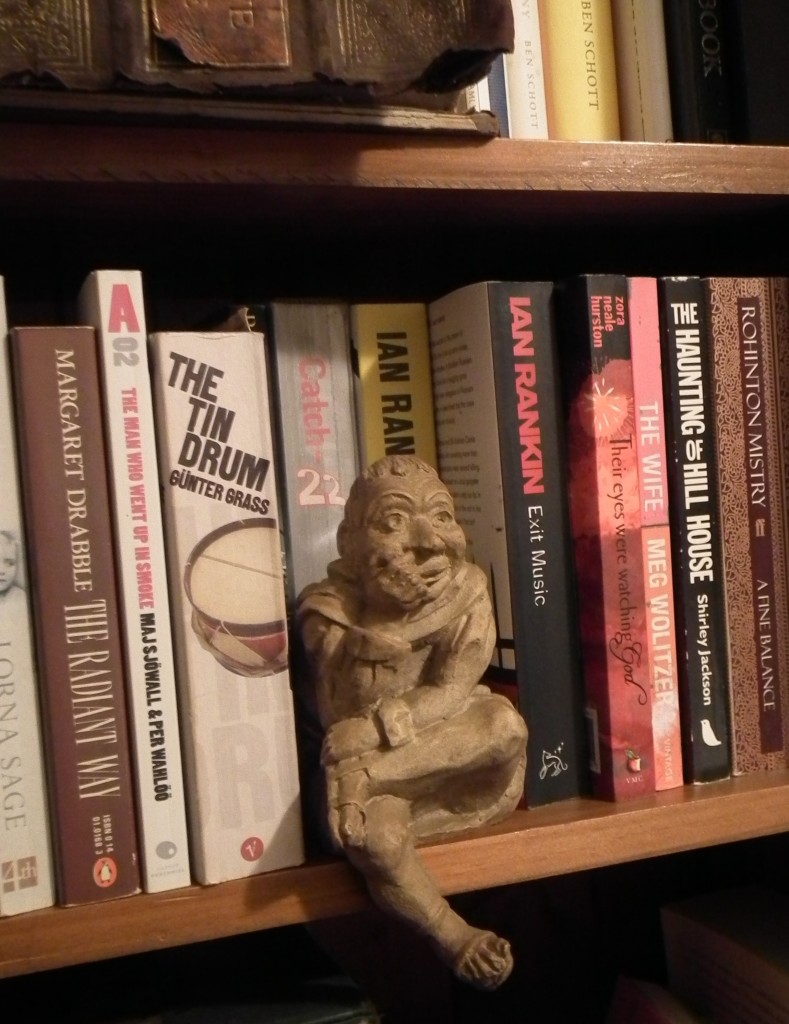

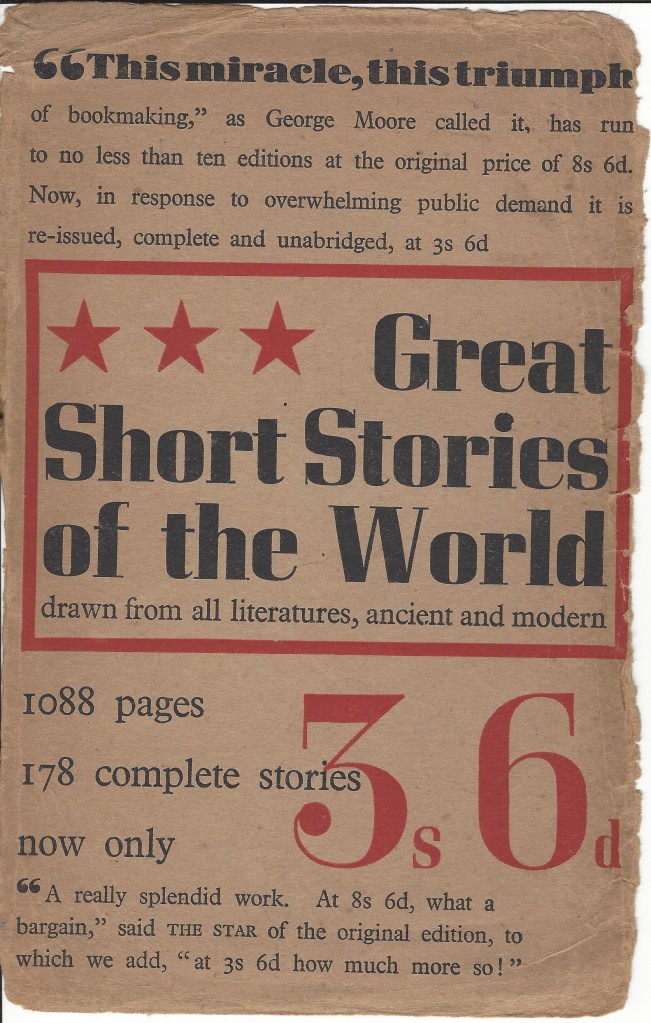

I’ve dipped into my 1937 copy of Great Short Stories of The World again, for my monthly post, and like Little Jack Horner, may have pulled out a plum. Allow me to share my visit to seventeenth century France, via Jean de La Fontaine’s fable, The Four Friends.

A little research on La Fontaine suggests he’s not been widely translated.

The references I found to his writing all describe it as poetic. The version provided for Great Short Stories of The World is by one of the editors: Barrett H Clark. He seems to have opted for economy, rather than poetry. I’ve had a quick search for other translations on the web, and only found simple retellings, often with sections blanked out so that it can be used for teaching grammar.

Which leads me to wonder if I’ve misunderstood Clark’s decision to use archaic words, and turns of phrase. I’d assumed that he was attempting to create a sense of antiquity, by including ‘disport‘, ‘whereupon‘, and ‘bewailing‘. Perhaps after all, he was trying to charm his readers.

The trouble was, I didn’t like his style. When the rat, ‘addressed‘ his friends, and in reply, ‘Up spoke the tortoise‘, it felt like an assumed voice, created purely for the sake of telling a story.

Tricks like these remind me that one of the first difficulties, when writing about the distant past, is choosing the voice of the narration. If the story is to retain it’s relevance to seventeenth century France, then maybe it does need to create a sense of period. But I’ve just flicked back one hundred and seventy one pages to find a contemporary of La Fontaine’s. Daniel Defoe’s 1706 story, True Revelation of the Apparition of One Mrs Veal was published in Britain, so has no need of translation.

There are a lot of words in Defoe’s story that could be considered difficult for the modern reader, mostly because our use of them has shifted. He uses ‘rare‘ where we might say unusual/unexpected/strange, or extra-ordinary; ‘relation’, here, means telling, or revelation. They work, and are understandable, because on the whole, Defoe’s narrator has a straightforward manner of telling. His story opens:

This thing is so rare in all its circumstances, and on so good authority, that my reading and conversation have not given me anything like it. It is fit to gratify the most ingenious and serious inquirer. Mrs Bargrave is the person to whom Mrs Veal appeared after her death…

Clark’s first sentence is:

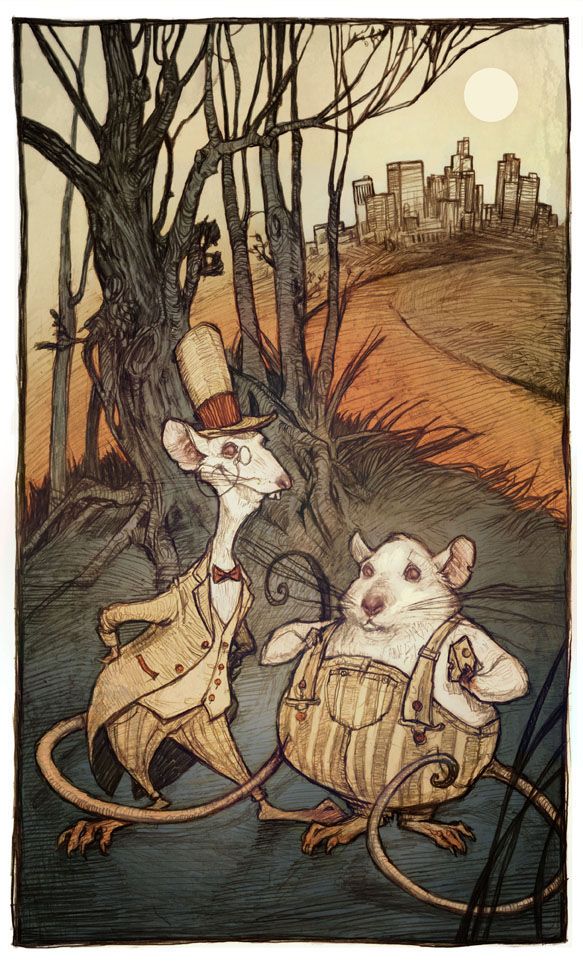

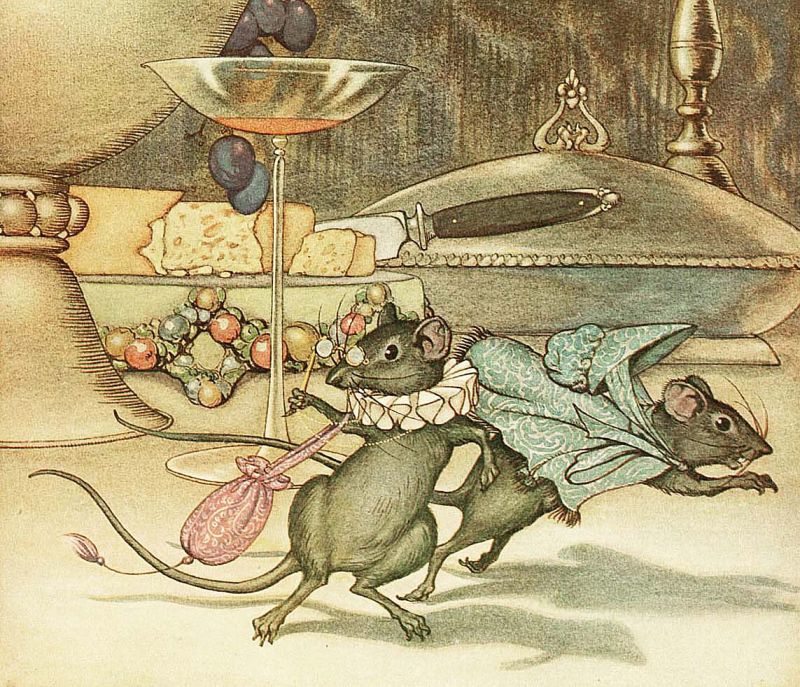

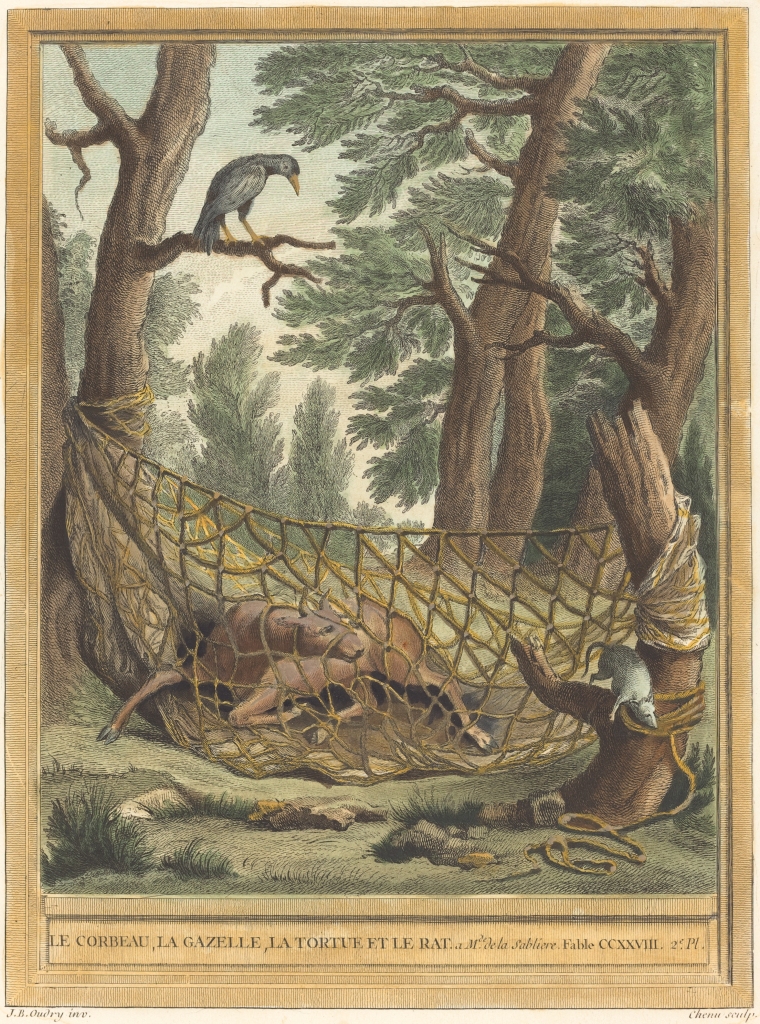

A rat, a raven, a tortoise, and a gazelle were once upon a time the greatest friends imaginable.

He has slotted what might be considered (by some) a traditional opening for this story into the middle of his first sentence. I’ve had a quick scan of the internet, and can’t find ‘once upon a time‘ in the original. So, call me pedantic, but I’m viewing this as a retelling, rather than a translation.

Having got my quibbles out of the way, let me say that I like this fable. It’s a short, and simple tale of friendship.

According to the Great Short Stories of The World, La Fontaine’s telling presents “a picture of human life and French society.” I now know that he, Racine, Boileau and Molière, formed an important quartet, meeting regularly at the Rue du Vieux Colombier. So this may be a symbolic representation of their connection. But, like any great story, it tells us other, more universal things.

This happy friendship first began in a home which was unknown to any human being. However, there is no place safe from humankind, be it in the densest wood, under the deepest river, or on the highest peaks where eagles perch.

In few hundred words, this fable presents a test, examines characters, explores consequences and forces me to think about my place in the world. I may be adding nuances and ideas to it that La Fontaine never imagined, but I’m reading and thinking about it two hundred and sixty-one years after it was first published, and not as a historical oddity, but something relevant to my experiences.